Not Just a Flash in the Pan: A zebra can travel at a top speed of fifty-five kilometers per hour, slower than a horse. However, it has much greater stamina. During the course of a day the plains zebra can walk around forty kilometers (from its herd, and back again in the evening)

Family Ties: There are four species, as well as several subspecies. Zebra populations vary a great deal, and the relationships between and the taxonomic status of several of the subspecies are unclear.

The Plains zebra (Equus quagga, formerly Equus burchelli) is the most common, and has or had about five subspecies distributed across much of southern and eastern Africa. It, or particular subspecies of it, have also been known as the Common zebra, the Dauw, Burchell's zebra (actually the subspecies Equus quagga burchelli), and the Quagga (another, extinct, subspecies, Equus quagga quagga).

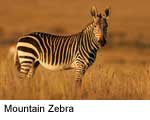

The Plains zebra (Equus quagga, formerly Equus burchelli) is the most common, and has or had about five subspecies distributed across much of southern and eastern Africa. It, or particular subspecies of it, have also been known as the Common zebra, the Dauw, Burchell's zebra (actually the subspecies Equus quagga burchelli), and the Quagga (another, extinct, subspecies, Equus quagga quagga). The Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra) of southwest Africa tends to have a sleek coat with a white belly and narrower stripes than the Plains zebra. It has two subspecies and is classified as endangered.

The Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra) of southwest Africa tends to have a sleek coat with a white belly and narrower stripes than the Plains zebra. It has two subspecies and is classified as endangered.Grevy's Zebra (Equus grevyi) is the largest type, with an erect mane, and a long, narrow head making it appear rather mule-like. It is an inhabitant of the semi-

arid grasslands of Ethiopia, Somalia, and northern Kenya. The Grevy's zebra is one of the rarest species of zebra around today, and is classified as endangered.

arid grasslands of Ethiopia, Somalia, and northern Kenya. The Grevy's zebra is one of the rarest species of zebra around today, and is classified as endangered.Plains Zebras are mid-sized and thick-bodied with relatively short legs. Adults of both sexes stand about 1.4 meters high at the shoulder, are approximately 2.3 meters long, and weigh about 230 kg. Like all zebras, they are boldly striped in black and white and no two individuals look exactly alike. All have vertical stripes on the forepart of the body, which tend towards the horizontal on the hindquarters. The northern species have narrower and more defined striping; southern populations have varied but lesser amounts of striping on the underparts, the legs and the hindquarters.

Striped and Social: Plains zebras are highly social and usually form small family groups consisting of a single stallion, one, two, or several mares, and their recent offspring. Groups are permanent, and group size tends to vary with habitat: in poor country the groups are small. From time to time, Plains zebra families group together into large herds, both with one another and with other grazing species, notably Blue

wildebeests. Unlike many of the large ungulates of Africa, Plains zebras prefer but do not require short grass to graze on. In consequence, they range more widely than many other species, even into woodlands, and they are often the first grazing species to appear in a well-vegetated area.

wildebeests. Unlike many of the large ungulates of Africa, Plains zebras prefer but do not require short grass to graze on. In consequence, they range more widely than many other species, even into woodlands, and they are often the first grazing species to appear in a well-vegetated area. Only after zebras have cropped and trampled the long grasses do wildebeests and gazelles move in. Nevertheless, for protection from predators, Plains zebras retreat into open areas with good visibility at night time, and take it in turns standing watch. They eat a wide range of different grasses, preferring young, fresh growth where available, and also browse on leaves and shoots from time to time.

Mountain Zebras are native to South West Africa and are found in dry, stony, mountain and hill habitats. Its diet is tufted grass, bark, leaves, fruit and roots. Zebras' dazzling stripes may be a signaling system for the herd and may also be useful in confusing predators

The Grevy's Zebra (Equus grevyi), sometimes known as the Imperial Zebra, is the largest species of zebra. It is found in the wild in Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia, and is considered endangered, partly due to hunting for its skin, which fetches a high price on the world market. Compared to other zebras, it is tall, has large ears, and its stripes are narrower. The species is named after Jules Grévy, a president of France, who, in the 1880s, was given one by the government of Abyssinia.

Sizes and Scales: The Grevy's zebra is the largest of all wild equines. It is 2.5-3 m from head to tail with a 38-75 cm tail, and stands 1.25-1.6 m high at the shoulder. Males weigh 380-450 kg, and females 350-400 kg. The stripes are narrow and close-set, being broader on the neck, and they extend to the hooves. The belly and the area around the base of the tail lack stripes.

The ears are very large, rounded, and conical. The head is large, long, and narrow, particularly mule-like in appearance. The mane is tall and erect; juveniles having a mane extending the length of the back.

The Donkey Connection: Grevy's zebra is similar to the asses in many ways. Behaviorally, for example, it has a social system characterized by small groups of adults associated for short time periods of a few months. Adult males spend their time mostly alone in territories of 2-12 km², which is considerably smaller than the territories of the wild asses.

The Donkey Connection: Grevy's zebra is similar to the asses in many ways. Behaviorally, for example, it has a social system characterized by small groups of adults associated for short time periods of a few months. Adult males spend their time mostly alone in territories of 2-12 km², which is considerably smaller than the territories of the wild asses. The territories are marked by dung piles and females within the territory mate solely with the resident male. Small bachelor herds are known. This social structure is well-adapted for the dry and arid scrubland and plains that Grevy's zebra primarily inhabits, less for the more lush habitats used by the other zebras.

Fighting for Females: Like all zebras and asses, Grevy's zebra males fight amongst themselves over territory and females. The Grevy's is vocal during fights (an asinine characteristic), braying loudly. Otherwise, the Grevy's communicates over long distances.

Just the Facts: The Grevy's zebra lives 10-25 years and eats grasses and other plants. Gestation lasts 350-400 days, with a single foal being born. Predators of Grevy's zebra include hunters and wild dogs native to the area. Most captive zebras in zoos are Grevy's Zebras.

Why Stripes? Originally, most zoologists assumed that zebras' stripes acted as a camouflage mechanism, while others believed them to play a role in social interactions, with slight variations of the pattern allowing the animals to distinguish between individuals. A more recent theory, supported by experiment, posits that the disruptive coloration is an effective means of confusing the visual system of the blood-sucking tsetse fly.

What's on the menu? African elephants are herbivorous. The diet of the African Bush Elephant varies according to its habitat; elephants living in forests, partial deserts, and grasslands all eat different proportions of herbs and tree or shrubbery leaves.

What's on the menu? African elephants are herbivorous. The diet of the African Bush Elephant varies according to its habitat; elephants living in forests, partial deserts, and grasslands all eat different proportions of herbs and tree or shrubbery leaves.  Thirst Quencher: Elephants also drink great quantities of water, over 190 liters per day.

Thirst Quencher: Elephants also drink great quantities of water, over 190 liters per day.

Human Predators: Humans are the elephant's major predator. Elephants have been hunted for meat as well as the rest of the body, including skin, bones, and tusks. Elephant trophy-hunting increased in the 19th and 20th centuries, when tourism and plantations increasingly attracted sport hunters.

Human Predators: Humans are the elephant's major predator. Elephants have been hunted for meat as well as the rest of the body, including skin, bones, and tusks. Elephant trophy-hunting increased in the 19th and 20th centuries, when tourism and plantations increasingly attracted sport hunters.  Birds and Bees: Mating for a African Bush Elephant happens when the female feels ready, an event that can occur anytime during the year. When she is ready, she starts emitting infrasounds that attract the males, sometimes many kilometers away.

Birds and Bees: Mating for a African Bush Elephant happens when the female feels ready, an event that can occur anytime during the year. When she is ready, she starts emitting infrasounds that attract the males, sometimes many kilometers away.  Classification Confusion: Until recently, it was thought that the so-called African Forest Elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) was simply a subspecies of the African Bush Elephant (Loxodonta africana).

Classification Confusion: Until recently, it was thought that the so-called African Forest Elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) was simply a subspecies of the African Bush Elephant (Loxodonta africana).

termites is found, the Aardvark digs into it with its powerful front legs, keeping its long ears upright to listen for predators, and takes up an astonishing number of insects with its long, sticky tongue—as many as 50,000 in one night has been recorded. It is an exceptionally fast digger, but otherwise moves rather slowly.

termites is found, the Aardvark digs into it with its powerful front legs, keeping its long ears upright to listen for predators, and takes up an astonishing number of insects with its long, sticky tongue—as many as 50,000 in one night has been recorded. It is an exceptionally fast digger, but otherwise moves rather slowly.